Semiotics is not merely a set of theories and methods whose aim is to explore and explain various meaning-making processes through detached analytical discourses. It is also a cognitive experience that affects our ways of perceiving and interpreting our surroundings and our social life. In the first text that is featured in this new rubric, Australian semiotician Geoffrey Sykes takes us to an intimate tour of semiotics in the first person.

A World of Signs

Chapter One: Nomadism in the Twenty First Century

By Geoffrey Sykes

Chapter One

“Launch out on his story, Muse, daughter of Zeus, start from where you will—sing for our time too.”

2nd June 2010. Caluzzi Bar, Sydney airport, 3pm

I am sitting in the Caluzzi Bar at Sydney airport, regretting the state of flight and fear anxiety that caused me to book in luggage some three hours before my 6pm take off on my carefully prepared, three week exodus to Bangkok, Berlin, Finland and Vietnam. I am writing this note in my black and red bordered notebook as if it were intended for some audience at some time, but actually it has only been an hour or less since I decided to start making a journal of this trip at all. Let me explain.

The first thing I did in this unplanned waiting at an airport (an experience now characteristic of citizens of the global village) was to check my personal effects. These were methodically stored in the two side pockets of the smaller bag that I had kept after checking in cabin luggage. It is too bulky to serve that purpose, and I should be shopping for a practical carry bag but there are reasons, as I will explain, for not shopping at present.

A passport (new, after weeks of searching for the old one; I will not leave this out of my sight), old travellers’ cheques (from an earlier trip 20 yrs ago), wallet and credit card, ticket, info itinerary, all located precisely in folders or alone in the zippered side pockets. Thus begins a habit of checking and over-checking that will occur many times each day.

The cabin luggage may be oversized, but it does have copious zippered pockets and sections, and on the side opposite to the two pockets is one longer section that comfortably takes unfolded A4 pages. In this sleeve are the three papers that I will give at the International Summer School of Semiotics, at the hotel Valtionhotelli, a Russian inspired castle-hotel situated on the Finnish side of the Russian-Finnish border, some 200 k north east of Helsinki. That is a main, perhaps the main, purpose of this international sojourn.

I browse one paper, highlighting the odd line and phrase in pencil but reluctant to undertake any process of revision: they are final drafts, they will do, although the first, titled, “Gesturing in an Indeterminate Field of Signs”, really does need some attention. But I am not in the mood to revise formal papers. The title, now read in this public place, pleases. It sounds appropriate as a conference paper title. So it should: the paper is the most original of the three, with a careful argument about fleeting body language in everyday talk. I feel and check for a memory stick that is securely kept in the bottom of the sleeve. I must have decided this would be the safest place for it. It is there. There are electronic versions of the paper on the memory stick, along with an additional paper published in the international journal of semiotics, Semiotica. I am very proud of that publication, and have brought the paper in case it can be cited or circulated in any way on the trip. There are also files of various unpublished notes, quotations, extracts, references to recent readings. The three papers are also located on an email account on my phone, and on a server – I have left nothing to chance and am well prepared. The content of the smaller pockets is valuable property, but the paper-clipped papers on the other side of the luggage are equally valuable in another way, as intellectual property. These papers are my passport to a world of ideas and perspectives that is just as essential as the blue document branded by the Commonwealth of Australia. With material clothing already checked, this satchel of ideas becomes my belongings, the lightweight dressage of meanings that will accompany my odyssey into the Northern hemisphere.

3.15pm, Caluzzi bar

Fifteen minutes have passed. I order coffee. I look around. The café is in a remote southern end of the renovated terminal. It is one I have occupied previously before a flight. Perhaps it is one of the more traditional cafes in the whole departure area. It is also quieter than the more public areas. I have been here before. There used to be a public telephone nearby which I have also used before a previous flight. The phone is probably still there but I do not move. The waitress is busy cleaning tables but finally looks in my direction and I gain her attention. A quick glance at a menu, an order, and pause.

I look back at the crowded vast inner atrium of the departure areas, from where I came less than an hour before. Seemingly innumerable check in row, branded by names and logos of international carriers: shopping arcades, information desks, and kiosks; toilets; cafes and restaurants; departure boards; customs entrances: all organised by a vast array of notices, labels, lists, directional indicators and brand names.

Signage. Signs. If this is my epic odyssey, it seems the way ahead is well plotted and mapped. Instead of unexpected encounters with creatures of enchantment, my voyage will be guided by a myriad of clear, well used notices. Instead of steering through imaginary landscapes, I am surrounded by an ocean of guidelines, boundary points, speed humps and channel markers. Every way out from this terminal to the world seems a familiar, well taken route. I know there are innumerable examples of pointing public signs, in our cluttered cities – starting with street and road signs. These seem commonplace and entirely functional. The trip to the airport seemed apparently predictable and straightforward – by rail from my hometown to the underground terminus, my short journey across the departure area. It was only until the airport atrium was negotiated – finding the check in, checking departure time, checking in, checking time, inspecting shops, finding somewhere to sit – that the journey seems more complex. Yet it looks like every sort of signage has been bottled and concentrated in the space of the atrium – at least I am suddenly aware of the environment of notices in which we breathe and travel. The environment of signs of the city, and the city railway, and the airport, are not dissimilar – both are complex landscapes built on a grid of possible and actual, individual and collective, journeys and pathways. Both can be represented in forms of geometric or diagrammatic maps. Layered within the geometric architectural shell of the airport is the intersecting grid of innumerable passengers and their schedules, and pre flight organisation. The only reason that the trip by rail seemed less complex is that it has been travelled before, either all the way to the airport or much more frequently through the main Southern line to Sydney that passes two stops from the airport line. Rail travel in one’s own city differs from travel in a foreign place: it becomes more habitual, predictable and familiar. But habits and familiarity can be a trap as much as a blessing – hence the adventure of travel, when the habits of one’s own home city and residence are left behind. The city rail network, or underground, of a foreign city, becomes as much an adventure in perception, logistics and imagination as the airport now appears to me.

If someone asked me, sitting here, for a quick, everyday explanation of what are signs in practice, I would need to look or point no further than the vast display conveniently close at hand in the airport atrium. The space is almost a laboratory of signs, and reminds me of Peirce’s early definition of sign as “something that refers to something for somebody in some regard.” This is his definition of the indexical or pointing sign, a sign being something that draws attention to something or somebody. This has been commonly expressed, in terms of a solitary sign, in a triangular graph. There are various expressions of this, including by Peirce, but their explanation of a sign function is more subtle than the simplicity of the graph suggests.

A basic function of a sign is to provide understanding about an object that is not immediately detected, known or present. As a scientist Peirce was interested in all sorts of gauges and devices that measure traces or conditions in the weather, or stars, or the land, that cannot be immediately seen. The same principle applies in the instance of an individual road sign – indicating the condition of a road ahead but out of sight. A gesture can point out directions to a traveller. Another gesture can gain the eye of someone who’s attention is absent. It works well in many instances at the airport – travellers search for the small gender drawings and accompanying direction arrows in their search for toilets that are located in recessed corridors. On second thought the whole airport environment is a signifying field indicating a panoply of world wide destinations, airlines, customs, departures and arrivals, and shops. Consider the potential references of signs presents in the main atrium. They point to remote absent destinations on the other sides of the world. Signs can have a micro range of reference as they operate in a conversation or cafe, but in the main business of mass travel they help organise travel at an international level. These codes, lists, indicators and labels are called signifiers. As sign objects they require an interpretant subject or traveller to connect to their potential meaning, and ensure a full sign function.

It is also true that a sign does not exist alone. It exists in relation to at least one other object, or place, or person, to which it refers – it connects a person to the world. Yet it also typically exists, in the way we understand and see it, especially in the busy constructed landscape of cities or airports alongside a host of groups of similar, different or competing signs all seeking to direct our attention: to a speed limit, a turn in the road, an intersection, a fast food restaurant, a sports fields, a factory, a shopping arcade. In a country with less strict town planning regulations, public and commercial signs proliferate like a world unto themselves, a “world perfused with signs” as Peirce said. If one disliked the visual pollution of cities one could call this apparently uncontrollable perfusion of street signage a virus, growing of its own accord. Certainly the experience of going through the airport departure hall and its vast arrays of signage can seem confusing. Hence my retreat to this relatively quiet corner.

Sitting here, I realize just how different flight is to other forms of transportation. The suburban train follows familiar paths which it reinforces. However efficient, flight is a long passage of endurance that becomes a process or way of life in itself. I look over a crowd gathering at a departure area. Some of them will be on flights or transit for the next 30 hours. In media res. In between the journey will assume a life of its own. We joke and prepare and compensate as best we can for long flights, but there is something still to be explained – in spiritual, physical, and anthropological terms – about this protracted experience.

I consider how the geometric elevated patterns of steel and glass rising from ground level to elevated heights perhaps encourage diagrammatic thinking in travellers, encouraging relaxation as well as distraction from the otherwise stressful practicalities of getting on board. Are the fluted colonnades some archetypical collective accompaniment to our individual pathways? What is this environment, this vast territory of space rolling out under the cloud like the ribbed ceiling of the sky above? There is something primeval and unexplained in the apparently modern and functional airport amphitheatre. Is this the tribal gathering of small families of travellers, gathered under respective airlines and destinations, crossing and re-crossing the vast concrete savannah plain and its latticed vegetation of check in booths, counters and shopping oases? If I am suddenly aware of signage, in this laboratory, and decide it is more than being unfamiliar or being less insecure. There is something anthropological in this ritual of human passage, through the neon Peloponnian cliffs.

Part of the café is now completely empty. A waitress stacks dishes, wipes tables, in efficiently mechanical physical actions that have become finely attuned by experience. She is about five tables, some seven metres, away. She looks overworked, and tired. She might have been on duty since 8am. Then she turns, momentarily stops what she does, and seems to ask me if I want another coffee. A lot could be said about the angle of the waitress’ head or elbow at that moment – more than I could recollect. Somehow, subliminally, imperceptibly, we invest quite a lot in such nuances of the human body. We can see in the quotidian vortex of body in space, in the mundanity of cleaning tables, a foundation of human experience as a whole. First, let’s consider a sense of sign present due to the waitress’ action that is not part of her communication to me. Before she looked up, the waitress cleared food, stacked dishes and wiped the table. In raising her head in my direction, the waitress does a remarkable thing. She directs the attention of her head and hand, previously focussed on the table, in my direction. That is, in the place of her precise relationship with objects in the world – the dishes and table – she establishes a relationship with another person – myself.

I indicate yes, she keeps working. I ask myself, how does she do this, or how did we do this? In the haste and space, how did we manage to exchange a distant request, and an answer to a request, as efficiently as stacking dishes? How is such a precise communicative exchange possible?

The linguist John Searle would give another explanation of the coupling of the waitress’ look and my response (which I cannot now remember). Together, he would say, they comprise a speech act. He classified speech acts – including promise, request, command, and question – that we use in everyday talk. The nearby family table is alive with promises, requests and farewells. The problem is that in the instance with the waitress no words were used. So let’s call it a sign act, rather than a speech act. Sign study has always had the advantage, compared to linguistics, of allowing the study of non verbal language, including the language of the body and gestures, pictures and music. The problem remains, what types of expressions took place, on this occasion, and how did we know how to deal with them? What was the angle of her head, or time, of eye contact, or posture, that precisely indicated to me her question? And how did I signal consent – that I was ready to order?

Part of the answer is in the immediacy and timing of the gestures and eye contact in themselves. Here everyday observation fails – we need visual aids, photographs, and video, to measure the micro nuances of our body at work. I make a sketch. Another part of the answer to my question about this moment is in the context or sequence of actions – the contrast between her looking up with the preceding physical acts of cleaning up.

Semiosis defines and operates in an ephemeral yet time critical space, between persons, or a human agent and the external world. Signs are like the imperceptible airborne minutiae that inhabit our immediate aerial space. To transliterate Peirce, the air is profuse with signs. Verbal and non verbal indexes are characteristically attenuated in style – compare personal and impersonal pronouns to longer etymologically derived nouns, or the ubiquitous ordinariness of a pointed finger to the elaborate routines of a choreographer. In order to function, indexical signifiers operate in a form of shorthand code that is familiar and easily recognised; for example, the lists and types of pronouns, the characteristic corporeal tokens, of fingers, arms and head, for pointing directions. There are non verbal grammars like there are verbal grammars, and non verbal grammars, referenced by their syntactical function, help explain verbal grammars. These simple punctuated and efficient speech and gestural acts are organised in set typologies and clusters, which we learn, in order to train us to the pragmatic use and effect of gestural acts, without which individual gestural acts could look odd and ambiguous and not serve pragmatic effects. In his earlier writing, Peirce used the notion of habit, to suggest a behavioural dimension of symbolic codes that offset the existential qualities and functionality of indexical signs.

“Gesturing in an indetermine field of signs.” Sykes, unpublished paper.

There would be a pause, separating the physical from the communicative acts. What would comprise a communicative act would be clear – why else would she pause and look up? Likewise there are limited reasons why she would look my way. The most fleeting, apparently spontaneous gestures can be coded. We are familiar with the type of gesture that indicates an order. It is something that has occurred in another café. A quick glance at a menu, an order, and pause. It is all very functional, neat this explanation of how we interact, neat like rows of street signs or airline names.

But it does not fully explain the aesthetic and precision of the act of ordering. There is a big difference between stacking dishes and the conscious act of ordering. However much one can dwell on biology and body language, both actions are highly skilled yet also highly different. What they have in common is respective body parts – head, hands, arms, eyes – and the absence of words. But a lot needs to be explained to know how a physical act (cleaning dishes) turns in a micro second into a communicative sign or gesture.

It occurs that what the ordering does resemble – its momentary intentness, the darting eye to eye contact, its focus across distant and all surrounding events – what it does resemble is the immobile alertness, the heightened awareness, of a primeval hunter who “took his bow and bent it for the bowstring effortlessly” (Homer). The search for drink and coffee, ordered in the vast open space, is a modernised act of hunting and gathering – or rather an act of huntings that is internalised, transformed and civilised as part of our communication skills. I decide there is more than meets the eye, so to speak, about the flow and passage of signs in the airport.

There is that word again. Sign. Our discussion of it could and probably will have many meanings, of culture, politics, religion, economics and transportation, and will take us to many places, and countries, but for the moment discussion commences in the most everyday setting of a café. William Blake, the famous English poet, once recommended the virtue of seeing “heaven in a grain of sand”. I seek meaning in a grain, or at least a teaspoon, of sugar. Sign. One virtue of the word is its embrace of the non verbal world, of pictures, hands, buildings and films. The linguistic does not quite extend far enough, to accommodate the moment that commences my travel. Yet this type of quick, direct gestural interaction is quite common, in the street, in shops, in traffic, in the workplace. The corridor nod, the consensual flow of traffic at an intersection, beckoning at a street stall. ‘Signs language’, it might be called – the capacity of a picture, of notice, of hand movement, to act as language, to function as words do in communication exchanges.

Somewhere before the arrival of my first cappuccino at the Caluzzi bar I made the decision that could be fundamental to the well being of my trip and perhaps to the well being of my career and my life generally. I have taken out that notebook (brought along for jotting facts and details), turned to find the first blank page, and commenced a journal of my travels. It will be both a documentation of events and a reflection on those events. It will record both a trip and an act of research and reflection on this trip. The trip might provide an unusual informal way of organising ideas, more so than the formal conference papers. This is what these notes now are: the actual journal written in hasty, rough handwriting first at a small cafe table, with the first pages mainly about the café table.

Time stops, a space is empty. I feel isolated in some far flung corner of a vast sea or plain. The coffee is delivered to the table. I stop writing, to notice the vast steel and glass atrium of the departure areas, on a scale typical of international airports around the world. What is the reason for a building whose size is so out of proportion to its function? The glass walls face to and from the tarmac – the building does more than provide a viewing platform for flights. Such a view might have been an attraction in the early days of 747 mass international travel, but does anyone want to look out of taxing planes these days? Is the interior of this place somewhere to empty thoughts, a larger than life green room before travellers are squeezed and catapulted by stimulus and drama on board planes and on to the other side of the world. My mind and perception wanders, to a large family group in front, where adults cluster and buzz in talk that is hard to overhear, and children move excitedly by a sense of change and farewell, and by the unexplored and vast space. Two businessmen engage in intense conversation. A couple exchange farewell greetings. Social events form and reform in a vast domain. The café is separate from the newish ones that cluster mid terminal, and is largely empty. This space, that discourages overhearing or even casual meetings, makes the architecture an ideal bubble or membrane in which the mind can wander, and miscellaneous everyday interactions occur.

I suddenly see a young traveller hunched over a pile of documents at a table. A solitary figure studies a map of what looks like a foreign city, along with various guidebooks and tourist brochures. The table is full of scribblings, notes, and pages of loose paper. The young man looks up. His look is one of cunning intelligence – mētis – of almost epic proportion. Suddenly the atrium is the quiet space of a vast research library, and all in it are engaged intensely in a intense and hushed study of charts, maps and guides of distant territory and space.

Daydreaming. Musement. This is a form of perception and state of being that Peirce, one source of ideas for two of the papers in my side folder, would entirely approve. Musement, as he termed it, is a process of loose, sometimes fallible, association of thinking and perception. It begins in an abstract space or page of possibilities. Formally he called this form of thinking abduction, but also used various informal names like day dreaming or intuition. Musing, I like that. I grab my smartphone. My one concession to digital culture. In addition to my satchel there is the little portal to wider learning. “Deep in thought. Contemplation, meditation’, one online dictionary says. I like “meditation” but am not sure of “deep in thought”. Then there is amusing, as in “entertaining, diverting”. Both amusing and musing are digressing and diverting: when we think we entertain ourselves. Both terms share a middle English etymology, to be idle, and an archaic Latin sense, to wonder or marvel. All senses seem appropriate to my daytime dallying: this apparently idle moment is suddenly significant and enriched. Yet the definition goes on, and links to the ancient Greek use of muse as the female god of arts, and in particular poetry. “Sing to me of the man, Muse.” It is a primeval sense, of being human, to be actively immobile, to rest in shadows or near water away from the fray of the hunt.

The ancient artistic sense encourages me to embellish my daydreaming in a further, literary sense, as a sense of stream of consciousness. I think of Robert Browning and Virginia Woolf, and sit more poised and nuanced in the plastic cafeteria chair. My confession might not have the literary pretension or seriousness of these authors, at least not for the present, but the link to poetry and writing seems to signify these notebook ramblings. I am also perplexed by the association with all things artistic. It is something I will undoubtedly return to: Berlin is on the itinerary for visits to the theatre.

“an element of observation; namely, deduction consists in constructing an icon or diagram the relations of whose parts shall present a complete analogy with those of the parts of the object of reasoning, of experimenting upon this image in the imagination, and of observing the result so as to discover unnoticed and hidden relations among the parts.”(Peirce, CP 3.363).

I sit back. Turn the page. However solitary the act of writing might seem it is not only a record of an inner world. It is an activity aided by the tools of writing, the notebook, and the environment in which it occurs. The same environment set up to facilitate high volume departures also allows reflection on possible flights or even impossible ones. It can be playful to notice airlines one has never used, or destinations never travelled. Tourism feeds off this sense of wonder or daydreaming about a hypothetical or possible way of seeing the world, and it is a sense encouraged through the arrays of notices, advertisements and signs in travel agencies, papers and here at the airport. The airport is a world of signs, and it is as easy to digress or dream, as it is to get on with necessary pre-flight tasks. The airport can be a good environment for imaginary writing, I decide.

I remember Peirce was so serious about understanding the nature of reasoning, the methods used in science and in everyday discourse, that he tried to develop a formal method or system of argument that relied on diagrams, to demonstrate a non linear dimension of apparently linear argument and talk. The diagrams were not only of the mind or logic: they were the myriad patterns by which the universe and the earth itself is known. The experimental scientist, the wandering surveyor of coastlines, planetary motions, natural forms. We are all cartographers, geographers, surveyors: we are surrounded by maps in this place. We buy, store, view, refresh maps every stage of the journey. We are always in media res, in between departure and arrivals, in a process of journeying. Nomadology – navigating a globalised world. Rediscovering our collective humanity. The facility allows us to pick up associations not planned or obvious, to vary or play with the neat, orderly pattern of travel. It also provides a form or field for thought. A blog. Anecdotes. Reterritorialising the globe. Defining world and national orders.

“Sing to me of the man, Muse, the man of twists and turns

driven time and again off course.”

Already my own notebook begins to look pleasantly full and disorganised. A laptop suddenly seems too organised to meet current needs. Notebooks feel eccentric and philosophical. I am glad the old faithful was left at home. I came to the quiet place in the departure area but have already filled it with thoughts and jottings of my own – my personal world of references and signs does not compete with the public clutter of the departure area. Rather than feeling enervated by the semiotic bedlam of the airport, I am now invigorated and feel right at home.

This trip has been carefully and ambitiously organised more than any previous international journey of mine. The planning of a trip exists in some pleasing if frustrating form of causative logic, that enables you to decide and predict where you will be, and sleep, and when you will travel, at what hour, many weeks before the actual trip. Within the travel plan is the detailed 4 day conference agenda that I received a week ago – I know within a matter of minutes when I will deliver each paper, in what room, and who will organise that session. There are still unplanned details – the hotel in Hanoi, a train in Finland, opera in Berlin – which still need to be booked. But these undecided details exist within a full itinerary, which ensures a probable and predictable outcome to the trip.

Yet the best laid plans permit gaps and idle hours. Lists are like that.

On a plane late at night, at a café in a hotel room, are unplanned gaps of waiting, resting, intervals for reflection. Musement. Jottings. Meanderings. I am suddenly fascinated by the plastic nature of time, and space. The best laid plan can be put aside, a continuum of time split into small intervals. On a planning scratchpad events can be altered, deferred, flights changed, time expanded as it is compressed. Travel is that, an experiment in time and space as much as a journey. This journal will be a log book of research into the experience of time and space, and I feel now it will become a main activity and project. I think I know myself (and my philosopher companion) well enough to feel these jottings will not end with takeoff.

It occurs again to me that I have drunk coffee at the table or one adjacent several times before, and made a call at the public phone nearby, in years before the ubiquitous mobile had become part of our hand luggage. Was a call then made to Veronica, a colleague of the South, or to Finland, or to some colleague here, or to all three? At one or at different times? If a call was made at the beginning of my first round world odyssey, to Veronica in Argentina, then Buenos Aires was some weeks away. I conclude it must have been a home call. LA, Chicago, Mexico City, NY, Buffalo, Buenos Aires. A long detour North to get back to the same latitude as home. But that was another trip, another time, another reflection.

3.35pm

I blink. Whatever I might make of my own half of the world, this trip is North. Time for another coffee. This might seem binge drinking, but a good shot of caffeine helps to get ahead of the rush of events, takeoff, information. The waitress is still preoccupied cleaning tables some distance away. Once again I manage to get her attention, and in a remarkably short period of time coffee appears. That time, between the characteristic confirmation of an order, and the delivery of the order, seemed no time at all. There was no room or need in the effortless transaction for a menu. I don’t remember what I thought or did in that interval – perhaps routinely or reflexively checked passport and credit card again.

Day dreaming is not dead time or no time. It can be a by product of efficient actions: when the conscious

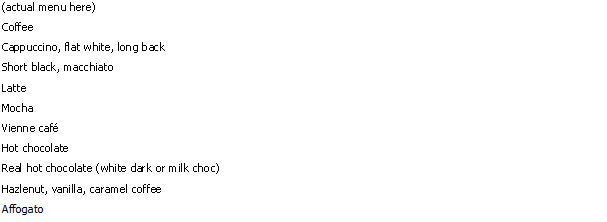

planned activities are completed ahead of schedule, when the crowded intervals of schedules seems less pronounced with the arrival of a second cup of coffee. When hunting is done, senses satiated, I stir sugar, then sip the nice broth or head on the cappuccino, and break the swirling pattern sprinkled on its top. It has an effect. I read the menu. When and why does one read a menu? Sometimes, like the present, I read a menu after ordering. A menu can be used to raise possibilities or to entertain, as much as to enable a efficient and quick decision.

My preferred order of coffee swings back and forth between mocha, flat and cappuccino – a matter of preference and habit that simplifies orders. For the past two years it has stayed the latter. The taste is one thing, but coffee drinking, wherever it occurs is more a ritual, an adjunct to at least three activities – socialising and conversation, work or musement. The particular type of coffee-in-itself can seem secondary to its function for social and personal use – another reason for doing without a menu.

In this case, the first touch of hot bubbly froth and colder hard edge of the cup to the lips seems to accompany and guide perceptions and thoughts in a rhythmic series of intervals. First I gaze around the southern walls of the area. ‘Caluzzi Bar’, I read on the walls the words I first saw on the menu. There is prominent strip of illustrated banners, with pictures of a city café. The name suddenly seems familiar – I realize I have visited a Caluzzi Bar already on several occasions. It is a small decades old shop selling pastries and coffees in Victoria Street on the south side of Kings Cross. The walls of the Victoria Street café are littered with postcards and greetings from around the world, along with signed photographs of celebrities taken on their visit to the cafe over the past 50 years. I contemplate, sitting at the airport table, the nature of the relationship – that one café points to, refers to or copies another.

I put down hot coffee and quickly go to the reception to pay bills and stretch my legs. Sometimes thoughts need spatial distance; there is a theatricality to thinking. She is confused. Our proximity motivates questions. “Is there something wrong?” “Is this the same coffee shop at the Cross? I have been there.” She looked surprised, as if in years of working no-one had asked. “No”, she said, “it is not owned by one person. It is a franchise. However the coffee is the same.”

Return to table, take another sip. This is good coffee. She is right. If the sole function of the name is the supply of coffee then it is worth the effort. For I do not understand how a franchise would work if the name was not known commonly. How could a small shop, an in-the-wall bohemian joint at the Cross, be a flagship for a travellers’ rest at the main airport in Australia? As Peirce suggested (in words to the same effect), copies ain’t copies, copies are always something else.

Too much fun. I suddenly feel marooned or misplaced, staring at pictures of old European street cafes when I am supposed to be flying to the place. I am like the Columbia space shuttle crew – they are locked away for hours on board waiting for the final few minutes of jet assisted take off. Part of me wants to get on with things, the other takes two steps back. Why dwell on a copy of a European street scene when the reality is two days away? Having exhausted myself preparing, somehow I am asked to prepare some more. To get in training, warm up, lay out and press the clothing of the mind as well as the body. Just as well by some intuition or fluke I allowed the time. What if I had arrived at the last minute?

But it is unsettling, to sit settled on a café chair for the first hour of my tour contemplating a commercial image as a sign. It is at least richer than the directional signage for toilets, gates, check-ins, luggage, shops and food that proliferate the surrounding floor space. Many directional signs have illustrations that copy or illustrate to show forth their meaning – the silhouettes of men and women at rest rooms, the arrowed pointing finger. Much could be said about the way we understand or perceive such pictures, especially when they are abstract drawings – such as the generic images of men and women. The faded black and white street café photo is no more detailed but perhaps less functional. This information quality is less to give direction than to embellish or decorate. The Sydney Caluzzi bar/café is part of the tradition of old streetscapes that extend from Sydney’s Cross, and its walls and style are much more suited to a place of travel and meetings than the open, uncluttered walls of the airport. The airport is full of personal stories, emotions, yet they are all dissipated or displaced by the vast, potentially clinical, emptied spaces. It is appropriate that the one café is a copy of another, and it of others; that there is a visual window to actual places of memory, visitations and greetings.

Another sip. How many sips are there in a typical cup? How does one use the rhythms of a cup to regulate a conversation? How does one balance a cup and talk, or balance a cup and write? How long can a hot cup last in terms of the temperature of its liquid? How long will I go on sitting here? There really could be a detailed empirical study of the use of a coffee in various activities at a café – its various uses as a tool for conversation, work or reflection. There are probably a dozen studies possible of the way everyday objects – chairs, cigarettes, hats, pencils, luggage, even phones – become part of role play in communication events. In the case of phones, they regulate not only talk at a distance but talk across a table. Even when there is no talk the phone-object can take part in surrounding ‘face to face’ talk. A phone conversation can also be mixed with surrounding live talk that is relevant or irrevelant to that talk. Multiple conversations. What is happening with the mobile at the adjacent family group? What etiquette or style is involved when your co-contributor to an extended discussion spends half or more of the planned, or expected time, on line to other places or persons. There is no-one else at my table, but conversation can be inner. You can talk to yourself as an extension or substitute for talk with others.

I finish a sip, lick my lips, take up a thick biro, turn the page of the notebook, and reflect about this sense of how café as franchise and copy makes it part of a whole. One understanding of copy as a sign is metonymy. A sign connects and relates places and persons, in this case cafes, and here a part of another place is present via a photograph. It is a fundamental human pursuit, to link one part of a landscape with another, to build associations and pathways. This sense of a photograph being an actual reproduction, a trace or small embodiment of its subject, is less common in our mass commercial society where photographs become commodities and objects of value quite apart from their original subject matter. They lose reference to actual places on the earth. Yet the evidence is that indigenous tribes first encountering a photograph really thought in fear that the image had stolen or taken part of the subject, and to some extent, there is a truth, that what the photograph captures, whether in celluloid film or in digital code, is a unique precise and actual impression of part of the reality of its subject. Metonymy. Or else, the copy makes homage and creates a richer sense of the original. Tribes fear photographs as they mirrored a spiritual or haunted image of their subject. Metonymy. Not an abstract symbol, but a virtual doubling of the self or place as a sign. The word should be better known. The weather vane directly registers impressions of the wind, hence in a way is changed and become an actual copy of that wind. A broken twig in the bush can be an actual trace and part of the movement of a bushwalker that has gone before. Sometimes great feeling and power can be invested in such memorabilia. Metonymy. How else do we understanding everyday life, our talk, our culture? Along with litter and visitors and directional signage, the airport is littered with metonyms. You find them in souvenir shops. Trinkets, momentos, objects. Not the teashirt with the graphic title of the country on the front, nor the small plastic replica of the Opera House, nor a cup with some vague picture. But bits of stone, wood, precious rock, fur, red meat, wine – some actual material part of the country, that reproduces or copies or stands for the country as a whole in a material way.

One more sip. Another interval. This is a mixed pleasure, fun but not. Part of me wants to bolt and watch six also ran movies on the BA 10 flight to Bangkok, pig out on every drink, snack, and meal offered, plus more from late night refreshments on the flight deck, re-read the airline magazine back to front ten times, consider buying a duty free watch to replace the one I left behind, doze, and generally veg and time out in economy – anything other than dallying about the nuances of meaning in some obscure commercial sign at the far reach of the terminal. But musement seems to have put the trip on hold. Like some temporal virus it grows in the expanded intervals within planned events. And this is only the first, of gaps left unplanned, or activities that defer to or even substitute for what is planned. I’m sure there will be many to come.

The family seated adjacent continues to be self absorbed, hardly noticing the layered effect of dimmed images on a distant wall. Perhaps a child gives them some attention. We must have some subliminal ability for these almost unnoticed and imperceptible images to have any effect. Not part of the subconscious so much as habits of thinking that have been trained and internalised. We do not need to be fully conscious of gestures or objects in the world for them to have meaning but importantly we can, if required, be so conscious. There are levels and degrees of vagueness and subtlety surrounding the focused, conscious brightly immediate world of our everyday selves. The picture in itself operates at a level of vagueness. We do not need to know the actual reference or café depicted – indeed what is confusing and ambiguous in one way is helpful in quite another.

The blurred photograph could be a picture of any café, a representative or blurred image of any number of street cafés in Europe or around the world. In this regard the picture becomes a type or symbol – one of a set, a representative of a group of images of all street cafes – it allows a generalised meaning to recur in a particular place, it gives what we call significance to a place. It also allows the image to become a commodity, that can be reproduced at convenience, and proliferating for profit if necessary. This recognition or knowledge, of the symbolic café, is not something mental or universal in itself – it is, like all signs, something we have learnt, when young or not so young. It is a generalisation from actual knowledge or instance, of direct experience. Souvenirs can be metonymns or symbols or a bit of both. A picture of the opera house (and there are plenty of those at hand in Terminal 1) is a representative of Sydney or Australia as a whole, as well as being a symbol or type of globally significant cultural object.

End of textbook chapter. Semiotics of everyday life 101. This thinking rolls out in full sentences because I have done it before, but never in a place like this. Not in everyday life. In lecture theatres, in seminar rooms, in published papers, yes, but never in a site that is the subject of study, never seeking a breezy and personal conversational style that matches that of everyday talk. It occurs to me that this table, however odd at first, could be more appropriate than the formal conference hall and art deco sitting rooms of the Valtionhotelli. ‘Semiotics’, from the ancient Greek, semeiotikos, interpretation of signs: actually the term ‘semiosis’ is as preferable. Back to phone: “Semiosis (from the Greek: sēmeíōsis, a derivation of the verb, sēmeiô, “to mark”) is any form of activity, conduct, or process that involves signs, including the production of meaning. Briefly – semiosis is sign process.” That verb sēmeiô – to mark – interests me a lot. I must return to it. The point is, for centuries semiotics, or semiosis, has promised the keys to unlock all kinds of traditional and religious truths, rituals, myths, sayings, meanings. It is an arcane tool of culture and civilization, a concept that Umberto Eco used to decode all kinds of medieval and ancient meanings in Romance of the Rose.

Yet signs are not only an esoteric part of high culture. In the first instance they are a dynamic part of our immediate observation and interactions. Charles said that the world is “perfuse” with signs, and once you get on a roll about their interpretation it is hard to exclude or see anything else. It seems to be quite suitable to write about it in streets and cafes. I return to the wall picture. Whatever else it conveys, or means, probably the main effect on the two businessmen still huddled over their intimate discussion at the table two to my right, is aesthetic. By this, I mean wallpaper. Eye candy. The visual pleasure principle. Decoration. On blank walls.

Two points about this point. As wallpaper or decoration we can assess the image as we might a painting on a home wall quite abstractly in terms of colour and composition. The photograph is vaguely of a café in another place, but equally a pattern of dots and lines, that fit in and complement the geometry of the wall behind whose structure it connects into a complex sign in itself, what can be called an abstract icon or picture that is the whole departure lounge. The modernist atria that comprise international airport settings are not unattractive. Sitting here, I look forward to seeing again the vaults of Helsinki airport thrusting up and against the birch forests and under mild summer twilight skies of the northern hemisphere. These glass cathedrals gesture towards unlimited expanses; they site and liberate our local selves within a grid of possibilities, an urban landscape, that extend like thin airborne wind blown tendrils connecting all places and persons potentially with each other, this universe of imperceptibility, and this semiotic globe.

One further association. One last sip of coffee. To make a literary allusion, our world can be measured out in coffee sips. Apologies to T.S.Eliot, but the allusion to the everyday world need not at all be as depressing as he made out, when his sad ageing character Prufrock measured out his life in coffee spoons. I am not quite aging, and not sad, and feel quite energised by this immersion in popular culture and a philosophy of language. Speaking of literature, the picture suddenly seems as if it were speaking to me personally, like the businessmen speak to each other, striking up some intimate association. I wait for this intended sense coming from somewhere else, this momentary synchrony of sense. Synchrony, a term coined by Karl Jung, the psychologist and interpreter of signs and myths of the collective unconscious. Synchrony, the uncanny sense of meaning and coincidence of events and persons that defies expectation and probability. Synchrony is a product of a world of possible connections, out of which one improbable association, that could only be called improbable or fanciful if contemplated before its occurrence, suddenly becomes actual. Synchrony, when objects distant in time and space find unexpected linkage or metonymy, when one becomes part of the other. It seems like the connections have been caused by influences out of our control, even though the result can be so personal. For example, we might think of a person we have not met for ten years and minutes later he appears.

In this instance, I remember now the second of three goals of the trip, that is to revisit and survey the experimental theatre of Berlin. Theatre. I remember why I ever visited the Calluzi Bar at the Cross. It was not to speculate about language, or rather it was to speculate about one particular dimension of language, which was theatre. Calluzi was a block away and round the corner from Griffin Street and the Griffin Street Theatre, a pokey hole-in-the wall esteemed small theatre space in inner Sydney, that has by Australian standards a long, four- decade old tradition of sponsoring if not new Australian work at least quality works that can be mounted in its five by five odd metre angled stage. Especially on a Monday night, when tickets are discounted. The whole experience included an hour train trip to Sydney, a snack and wander along the other side of Victoria Street through the seedier strip of the Cross, coffee at Caluzzi, then theatre – a pleasant and affordable start to the week. It seems uncanny, this personal association or memory interpreted and unlocked in the dim outlines of a public display. I look up. Suddenly the two businessmen pack up their laptop, end their affable talk and leave hastily. Flights approach, but I am still taxing. I haven’t heard a word they say – the space seems designed to distribute or muffle noise to allow privacy within a large population. I remember I am acquainted with a boffin like individual who designs acoustics for the airport. Is his concern with PA or with the sensitivities of speech acoustics of the space in the departures of travellers? I am left to my own peregrination. I’m warming, or whatever metaphors apply. Comparisons such as metaphors – comparing one thing with another based on some feature – are motivated by intense feelings, but at the airport there is enough real and unexpected, enough direct and indirect, to not need metaphoric embellishment. Within the plans, the preparation, the everyday theatre, is a package of aspirations, meanings, effects and signs that is actual theatre. I sip at the thick layer of froth at the bottom of the cappuccino. It is always welcomed – usually gouged out by spoon, or finger, a slurp, or last sip of the tilted cup. It is not at all a despondent gesture, more a slightly poised eccentric alert and faint gesture to bohemia.

Whatever. The gesture to theatre is probably the most appropriate of all the allusions possible about coffee drinking. At the end of the day, coffee is coffee, and at best a respite or supplement to life as a whole. Some people might have elevated coffee drinking to a social ritual and end in itself – but that can’t be the case at the airport, where after almost two hours of drinking the big picture still awaits. The café is a greenroom for the main act which is to follow. All that has happened, all that is ahead. Actually about life, and theatre. How theatre and life relate. The signs of both.

4.20 PM

I’ve been here well over an hour and a half and the sense of time and space has changed. Time has been compressed and space clearly expanded. I get up to stretch my legs and check the actual time. Chronological time beats at a steady rate, of its own accord, and I must check in to its counter on occasion. I have forgotten my wrist watch, and vow to buy one. The phone has a leather case, and it is annoying to salvage it all the time. Standing, I look down at the notebook sitting near the empty cup and feel a sense of belonging, an almost sentimental attachment to a place and sense of valued time passing. If I left the airport now to go home, I would feel the visit here was worth it, not of course as a substitute for the trip as a whole, but as an event of interest in its own right. I cannot believe there are pages written that were not planned or conceived several hours ago, that a project has been born in a peripheral empty part of a transport terminal, that this backroom ad hoc research into how we connect to the world and make meaning has begun in the way it has.

4.30 PM

I check the clock at the service counter, return to the table, and begin to pack up when a sense of deja vu binds me to the chair. The space seems to be signalling some further sense. I look around again. Have I missed something, or someone? Has someone just sat down? In fact, it is my memory that holds forth. In an age of mass transportation travellers are usually serial fliers. They do not come to their capital city airport once – despite the airline name there are relatively few “virgin” fliers. Visits are not as special as they might have been in earlier decades. Travellers and visitors come on numerous and often forgotten times. Visits become rituals and sign posts for families growing up, for the stages of an individual’s life, comparable to rites of passage such as baptism or marriages. The aerial atrium truly is a secular cathedral. Airports might be a transitional zone, but one visit can be between or in an interval of ones that have already happened or have yet to occur. One visit links or connects other trips. Although my memory is vague, the sense of sitting in this café before returns. When was that time? Was it before my first trip to Finland, seeking out talk about Charles? Or Thailand, on another flight? Experimental performance at the Volksburn Theatre in the old East Berlin? Or a five hour long expressive joy filled seminar on expressive joyous body language in Beunos Aires. Or a lecture on icons and symbols to the Slavic Institute in Moscow? Or a visit to the home of Charles in Harvard, USA? All these places have already been hot spots in previous pilgrimages of study and inquiry. All or some or any one of them might have commenced at this place. Is this trip a re-run or fulfilment or effect of one’s or others’ past? What connects the past and present, the present and the future? What makes a life whole?

4.45 Food court

I brush aside for the moment this larger tapestry and trajectory of memory, history, destiny, and past and future possibilities. I could probably take notes in this one place for another three hours but this is not an option. There are parameters and rules limiting idle time. Vagueness cannot be all, otherwise delusion would rule. Sign experiences intersect, the indirect thought with the direct need to board. Out of the intersection of types of language, consciousness arises. Stream of consciousness is the correct word, to describe immersion and awareness of the world as systems of signs.

In my side folder there is a print-out of a draft paper, “Culture as Territory: Re-exploring the Human Condition.” The paper is sprinkled with phrases from a favourite French author, Gilles Deleuze. How human emergence or evolution can be started as a process of constant reterritorialisation of the territorial sense of other animal species. How all animals are receptive to signs, and how the intelligence of our prehuman ancestors was doubly receptive to signs of other species. Our ancestors travelled and moved forward: they lived in what he called “a vector of territoralisation” and journeyism that is represented in fluid diagrams. I consider how to travel today, across continents, efficiently, is a modern act of reterritorialisation that is at the limit of our social understanding. In flight we are moving in a border of between our familiar thinking, and a strange non thinking that has much in common with the nomadic state of our human ancestors. I remember Deleuze said a lot about nomadism, and probably coined the term nomadology, although I will not confirm the latter observation just now.

The airport is a location, an interaction of space and possibilities, but I have been sitting in one particular place for over an hour and a half and suddenly some small anxiety kicks in like some reactive panic that I should be someplace else. I move on. I am not sure where this bolt of anxiety comes from, but come it does some hours before any flight, however well prepared I might be. Is it some genetic, primeval urging, of survival? Some self monitoring and warning about over indulgence in time wasting? Some legacy of being in a mobilised campaign whose details and strategies require precise attention? I leave, pacing by long, steady footsteps through a broad promenade of shops, check in counters and other eating places. I progressively push, if not barge, through a phalanx of travellers and their company together on this side of the frontier of customs. As you walk you quickly lose tacit or comfortable knowledge of what comprises “home” – the clusters of familiar and internalised habits that make up everyday commonsense. You begin to lose it somewhere between the city train that brought you to the airport, along the familiar, routinised length of a branch line into the Sydney southern suburbs, and this congested mingling and hubbub of the departures area.

I sit down at an unattended table in a vast crowded restaurant area that is not unlike the mixed food offering at a suburban shopping mall. Japanese, Thai, Indian, Korean – you don’t need to travel far to have an international taste sampling. But this is not a place for culinary sampling – it is more a site for muddled mass munching than musement. Departure might be a melting pot of different cultures, but there is no sense of overall intercultural celebration. What rules apply for this rambunctious social gathering? What are the social rules?

Recapping and making new notes, my writing changes: it is fluent, fast and episodic – like small portions of fast food. It is digestible, its style responds to the environment. As it grows it evolves. Energy and lines compete with the ebb and flow of peoples. A prior premise, that to survive travel one needs to become an expert, is reaffirmed. An expert at a practice and theory of interpretation. Of signs. Of cultures, of peoples. You need to understand. The world is a research library. How you are being directed, connected and organised. With others, with airlines, with the rest of world. Travel is a thoroughly semiotic affair. The airport and its atrium are a training space and incubator. Travel is a laboratory. Each of us are researchers and translators of language and signs. We seem to enjoy this ‘meta’ state. It is as natural as our native language, to be a translator. Globalism has not produced a level playing field. The globe is a crowded proliferation of the competing, different social worlds. Each port of call is a vast plateau or planet in a galaxy of signs that the world comprises. No hierarchical or colonial order – perhaps with the exception of English. The planets in this constellation may mix more but the result is complex.

I stop. Odd phrases go on and on in my head and on paper but seem too unfocused. I look around. I feel trapped. In cafes, shops, foyers and walkways you try to adjust, focus and follow. Children run in circles. Adults ponder or hug. Chapters in a hundred epic novels of travail, hope and separation are played out. History is enacted, autobiographies unfold, lives become. You only have to see, and listen. The vast cacophony of social life growing organically in this cavernous incubator. Between the familiar and the unfamiliar. I seek inner direction in the outer indicators of flight, rest rooms, customs, duty free shops and fast food. Awkwardness, idleness, and passionate emotions are played against physical anxieties of flight time, practicalities of luggage and security of belongings, announcements, endless refreshments. I feel trapped. Overwhelmed.

I conclude the atrium space invites three states: free thought and musement, hectic intensive interactions and actions, and various rules that organise behaviour overall. Most of the latter have to do with departure procedures. These states, one indirect, the other direct and communicative, the third social, seem fundamental to our ways of seeing and knowing the world. But under the weight of the second, hectic competing meetings and small groups, I feel trapped, breathless, by the sheer quantum of activity. I need to move.

5.20 pm Seat after customs

Funnelled from the larger space in narrow gates, queues and a low ceiling. The familiar world, the habitualised or naturalised routines of everyday life, of one’s ‘native’ language and region, are left behind at customs at the place of departure, and what one enters is a narrowed, gated, de-naturalised, bared, exfoliated world of codes, passports, instructions, security, inspection – a strangely conformist and obedient ten minutes trial. It is a ritual, a rite of passage, sanctioned by international government order. There is no confusion about rules. Rules are unusually declarative, motivated by security, national borders and customs. The membrane of self and expression is scrubbed bare and exposed, along with the contents of one’s baggage, in the first exposure to customs x-rays. This exposure, this baring of the body or layering of language that we usually wear in comfort, without embarrassment or self consciousness, has in varying degrees been peeled back, discarded, folded or hung up, as another layer of barely perceptible clothing.

The nature of this experience, whether akin to being incarcerated or even terrorised by strange environments of language, or liberated in some ritualised transcendence of one’s own familiar world, is not fully known at the first departure, except as a frisson, an excitement and nerves. In addition to constant checks on the documents and finances of travel, accommodation and food arrangements, as well as physical safety, it is the excitability of travel into a realm of unknown and unfamiliar signs that is a major source of nervousness and excitability, before and during any trip. Despite all the efficiency and mass organisation of international or global travel, this journey into different horizons of expression and language remains as strong and unsettling as it ever has been, and with opportunities for quick and cheap travel between time zones and continents, if anything fatigue from the lag and proliferation of signs remains as potent as fatigue from time zones and physical relocation.

I have passed through. I am writing from the other side, a liminal, hidden domain which only those certified and sanctified can enter. Is this Australia, or some further layer of transition? It has been a wait, an expectation and an effort to get this far, but the vista is quite disappointing. Duty free. This world is a wall to wall shopping centre. The empire of shops extends triffid-like commercial tendrils beyond nations and localities. It binds nations and territories. An umbilical cord has broken, but I am connected into a jungle of vines of global capitalism. I have to wind my way through wall to wall displays of duty free. These islands of the Lotus Eaters crop up throughout the Peloponnesian passage of international travel, trying to satiate the adventure of a long distance quest with the endless seduction of luggage, clothes, souvenirs, perfumes and liquor.

The Mac stand has an empty space. I spring from this precious seat. A chance to test the Ipad.

5.35 pm Bookshop

I am at a bookshop, somewhere on the way to gate 19, scribbling between rows of travel, cooking, new release novels and classics. Will I ever get to the flight? Will I survive the next nine hours to Bangkok? Everything seems suddenly protracted and long. This scribbling habit might come to a sudden halt on the plane. I choose a novel as a safeguard. Trust the blurbs, probably big mistake, best British novel of decade. Indeed. I become quite expert at jotting on the run, and my handwriting becomes progressively dashed and execrable. I am glad I left the laptop at home and don’t need to be switching on and off, worrying about batteries, and writing uniform lines and neat fonts. This scribble is much more fun and flexible, and quite literary, even quaint. I assume a role of the roaming author and global flaneur. But how strange, writing in a notebook amidst the new releases of an airport bookshop, having spent the past 20 minutes testing out the new Ipad at the Mac stand. They all seemed too neat, the packaged laptops, netbooks, Ipads, Iphones, cameras, accessories. The stand is first up near the customs exit, as if electronics were more essential for international travel than leather luggage. I re-checked my smartphone – safe in the side pocket it is, although no one has rung for the last three hours, and I have tried to use public clocks and flight boards for the time. Will be glad to turn it off on the plane. I spend most of most days transfixed to an LCD screen. Reality is suddenly a long interval between telecommunications. This trip will allow me to renegotiate and reconsider my heavy involvement in all forms of electronic devices. The Ipad seemed so dim and colourless compared with the colour of the bookshop. I am suddenly a convert to literary culture and have yet to be converted to the advantage of reading prose on a digital pad.

The thought crosses my mind that I could be doing this as an online diary or blog. Right. Who would read such a thing? Who would want to read twenty pages of caffeine induced speculation before I have boarded the plane? What photos would I supply? High res. images of a coffee cup, or a takeaway? My boarding pass? I choose to savour my words, perhaps edit, extend, amend, my moments in airport cafes – in good old fashioned literary style. I’ll blog the universe first before I market ideas in my own street.

First person yes, but not as a blog. First person is unusual enough. This is the first time in first. The voice, the ego, the self, the unconscious, the subjective, the stranger? The perspective as far as writing goes seems taboo or embarrassing. Really, despite vast tracts, never in first. Fiction and papers have always been in third person – I begin to think of myself now in third person, as a character on my own trip, but need to consciously stop using “he” to refer to myself. “He” stood at the bookshop, productively filling in time. My cousin Denise is a counsellor and she thinks a more personal style could be therapeutic, good for me, help me express feelings more directly. She thinks that my existing oeuvre of papers and plays is too formal and impersonal. Not sure if this is what she had in mind, but I will tell her of this breakthrough in style, the end of a writer’s block of self. I glance at all the first person genres on offer on the surrounding shelves – travelogues, autobiographies, chronicles, cookbooks, journalism. I am in good company, and decide then on a subtitle for the three hour long opus – a world of signs. Sounds catchy. The main title still eludes.

I notice a shop nearby retailing aboriginal souvenirs. A familiar yet welcome display of paintings, prints, painted didgeridoos and other indigenous artefacts. The familiar style of dots, markings, scribblings and sketched lines fills the shop – the art work is a diagram, and a representation of a world and landscape seen in the first instance as a diagram. The dreamtime transformed the natural landscape of the Australian continent into a pattern of tribal paths, mythic features and personal journeying. Modern and dreamtime stories and meanings are marked and deciphered within the diagrammatic forms. There is something very modern (and semiotic) about the cultural forms of this most ancient people, and our neighbours in the Southern continent. I feel satisfied at this last glimpse of the tourist mall – it is some compensation for the commercial overtones of the arcade as a whole.

It is a pity the artefacts must be seen quickly and at a distance – the chronology of take off kicks in.

Sudden flight and fight instinct kicks. Have I digressed too long amidst myriad manuscripts? Have I digressed too long and forgotten the main goal of being here – to board a plane? What time is it? Is boarding delayed? Have I missed the call? Where is my wrist watch? Where is my phone?

‘BA Flight 10 to Bangkok now boarding. Will passengers please make their way to gate 30?’

Where is the gate? Literal time and space seem strange commodities. Here I am, desperately seeking gate 30 and all that is on the other side.

5.50 pm

Boarding pass and bag in one hand, notebook in another. Home. The primordial survival sense was soon neutralised – by some intuition or good luck I was very close, metres away, from the purpose. Have been in a way for hours. No sweat. No worry. I breathe easy, and deep.

There is a queue, more a clan than a queue, strangers to whom I will belong for what will be compared to the last three hours, an epochful journey to the embers of Civil War in Bangkok, and the embers of world wars in Berlin and Vietnam, and the search for meaning in Finland. The queue is thick now, and I look around in case there might be someone I already know. I check again luggage on both sides, and balance the coat and the packaged book on alternative elbows, and proceed to board.

“Direct me, put me on the road with someone.”

Geoffrey Sykes (Editor in Chief – Southern Semiotic Review) has lectured extensively in communications, semiotic, media and cultural studies, at the University of Wollongong, University of Western Sydney, Notre Dame University Sydney and most recently, the University of New South Wales. He has given numerous guest lectures and conference presentations. His doctorate on the seminal semiotic figure Charles Peirce received strong international reports. He has had over thirty papers and book chapters published, including refereed journals such as Semiotic Review of Books, Canadian Journal of Communication, Media International Australia, American Journal of Semiotics, and the Journal of Philosophy of Education. He has successful experience as a filmmaker, with broadcast credits screened nationally by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, as well as on SBS television, Arts NZ and Foxtel. As a theatre writer and producer he has over 35 professional theatre credits. Along with other interests, he brings arts and media perspectives into the journal.

Southern Semiotic Review was founded in 2013, and has published over 80 contributions from over 55 authors. It has an established editorial team. It aims to meet a need for a dedicated journal of its kind in Australia and its region of the world. It also has an inclusive international reach.

This journal is fully international in focus, and responds to the promise of semiotics at many levels – philosophical, educational, conceptual, cultural, social change and self understanding.

It also responds to a perceived need and opportunity to develop a more comprehensive approach to the study of semiotics in Australia—and in other countries more distant from mainstream traditions and practices in Europe and North America. This appears to be the only journal of its kind in this country, and, as a general inter-disciplinary English language publication, perhaps in the Southern hemisphere.

The journal is general and international in scope, and special issues and themes will be conducted in addition to general issues.

Themes include arts, media and mathemesis, theology, communication, and polis. Acceptance for special themes is continuing, and respective themes rationales are available.

The ‘southerly’ tag in our title is also intended to connote, in the Deleuzian sense, emerging networks and expressions of culture and communication generally, governance in our global public life as well as expressions of identity in international and local contexts. We anchor our policy and editorial practice in seminal figures of modern studies, in particular Charles Peirce.

www.southernsemioticreview.net

southernsemioticreview@gmail.com

Be the first to comment